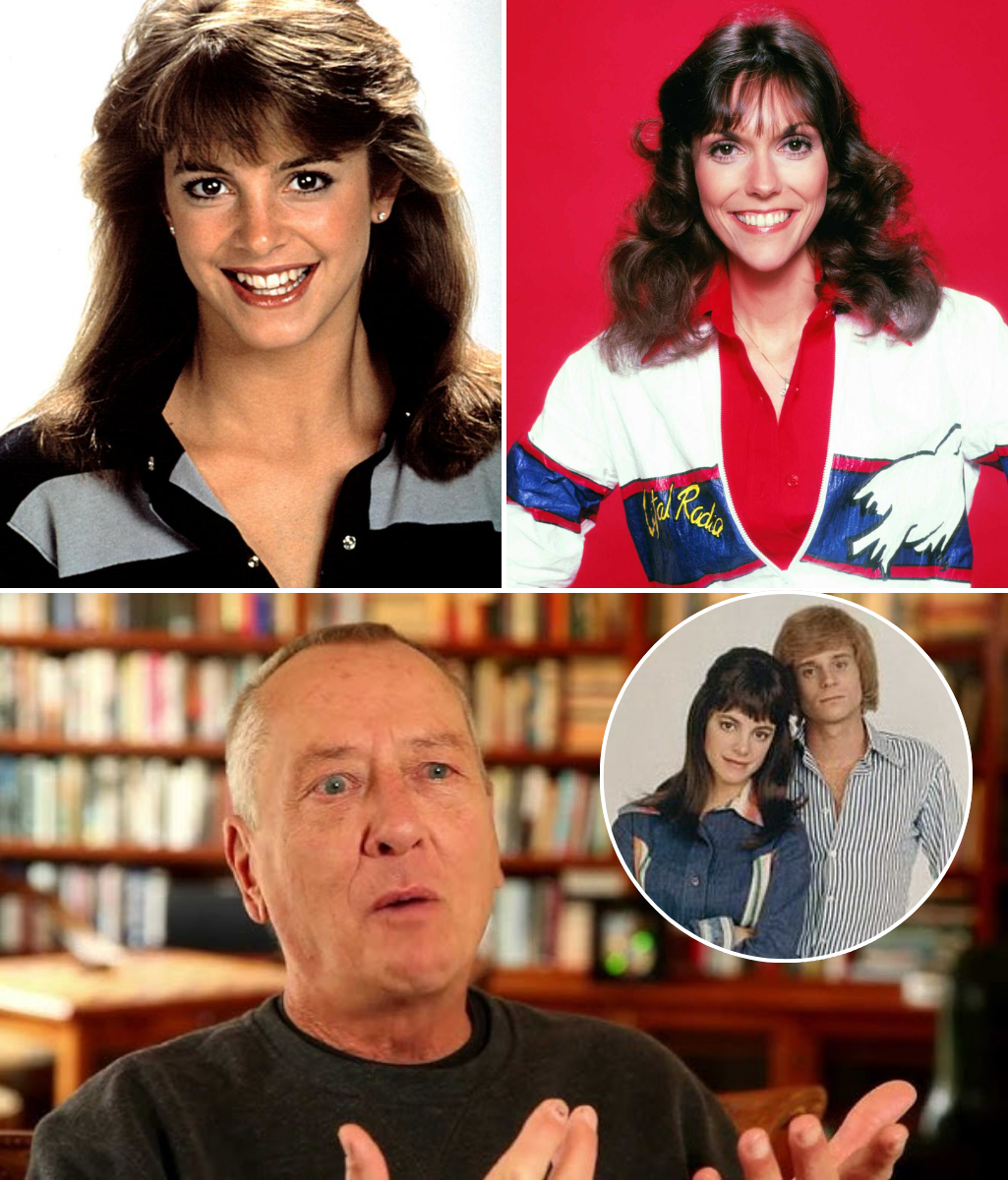

“I Had No Idea What I Was Walking Into” — Barry Morrow on Writing The Karen Carpenter Story

Jerry Weintraub called me. That alone would’ve been enough to make most people drop the phone. But what he said next stopped me cold:

“I want you to write the Karen Carpenter movie.”

I said yes, of course — anyone would. But truthfully? I wasn’t ready. Not for her story. Not for the silence that wrapped itself around her name like a curtain no one dared part. I had barely found my own footing as a writer. I was just shy of thirty, fresh off a film called Bill, a quiet little gem with Mickey Rooney and Dennis Quaid that somehow exploded into awards and unexpected attention. I had stumbled into storytelling by accident — and now I was being asked to excavate the life of someone I barely understood.

Here’s the thing: I wasn’t a fan. Not out of dislike — more out of ignorance. The Carpenters? Too soft for my ears. Too sweet. I was raised on Dylan, Springsteen, and the smoky heartbreak of Nashville bars. The 70s, to me, sounded like guitars bleeding truth, not elevator music whispering pleasantries.

But Jerry… Jerry had a trick up his sleeve. “Do you like wine?” he asked.

I said yes — even though I barely drank. “Good,” he said. “I’m sending you home with the best bottle you’ve ever had — and a stack of Carpenters records. Lock the door. Pour a glass. Just listen.”

So I did. And something shifted.

Karen’s voice — it wasn’t soft. It wasn’t sweet. It was aching. Beneath every “Top of the World” was a tremble. A contradiction. A silent no, I’m not.

And then I heard Goodbye to Love… That guitar solo? It shattered whatever idea I had about who she was. It soared. It burned. And it was lonely.

That weekend wrecked me.

I called Jerry back. “I’m in. Let me at it.”

But I told him, straight up: “I don’t know anything about eating disorders. I barely know Karen’s music.”

He said, “That’s okay. You’re honest. That’s all I need.”

What followed wasn’t a screenplay. It was a war zone.

There were so many gatekeepers. Richard Carpenter. The network. Lawyers. Family. Friends. Everyone wanted their own version of Karen’s story — the safe version. The one where she smiled and sang and stayed on key. But the truth? The truth was tangled. And I had no allegiance to anyone but the truth — or at least, the why. Why did this brilliant, gifted, ethereal woman die?

I thought I’d get help from her family. I was wrong. Richard — brilliant, calculated, a musical architect — wore a mask I couldn’t penetrate. Even in his own living room, with coffee and cookies and notepads between us, it felt like I was interviewing a CEO, not a grieving brother.

Agnes — Karen’s mother — was polite, guarded. She gave me nothing. Harold, the father, barely spoke. The most devastating moment? Sitting across from them, asking what Karen’s last days were like, and getting… silence. Formalities. Deflection. As if her death had happened in another household.

I failed that first interview.

So I went elsewhere. I tracked down Herb Alpert, others who’d brushed against her light. And then I found Frenda. Karen’s best friend. A talker. A truth-teller. And thank God.

Frenda didn’t give me Karen the icon. She gave me Karen the girl — the quiet insecurities, the goofball humor, the tiny victories that would never make headlines. She knew the private Karen. The real one. And she was terrified the world would turn her into a myth instead of a memory. We talked endlessly. I mostly just listened.

The original script? It was rich. Layered. Honest. But Richard wasn’t having it. Draft after draft was stripped, softened, neutered. The sharp corners — gone. The family? Untouchable.

Eventually, Richard came to me with an offer. “I’ll give you something about me — something real — if you back off my mother.” He admitted to an addiction — to Quaaludes — and allowed it to be written in. It was his olive branch. And his shield.

I couldn’t make that deal. I wasn’t writing The Richard Carpenter Story. But the network? They agreed.

Then Joseph Sargent came on board. A fearless director. And his first move? Cast Louise Fletcher — Nurse Ratched herself — as Agnes. It was poetic. Louise could say “Karen, dear” with a dagger behind every syllable. She became the mother we had tried so hard to write around.

Some moments we invented. That scene where the psychiatrist begs the parents to tell Karen they love her — and Agnes can’t say it? That wasn’t documented. But it felt true. Tragically, heartbreakingly true. Because that’s what the music said. Not “I’m happy.” But “I’m longing.”

And that final “I love you too, Mom”?

It was fiction. I know it was.

But sometimes, you invent closure — not to lie, but to help the audience survive.

This wasn’t exploitation. It was a mirror. And for some viewers, that mirror saved their lives.

Doctors reached out. Psychiatrists. Families. They told me this movie — flawed, stripped, rewritten — still opened eyes. That Karen’s story had named something unspoken.

Anorexia wasn’t vanity. It was a disease. And Karen made it real.

Do I wish we’d told the real story? Of course. Do I believe Agnes ever said, “I love you” to her daughter? No. I wish she had. But I don’t believe she did. That kind of love — it wasn’t spoken in their house. Not out loud.

But we gave people a version of the truth. Not the whole truth. Not the perfect truth. But enough.

Enough to feel her ache.

Enough to remember her name.

Enough to save someone else.

And for that —

I’m glad we made the movie.