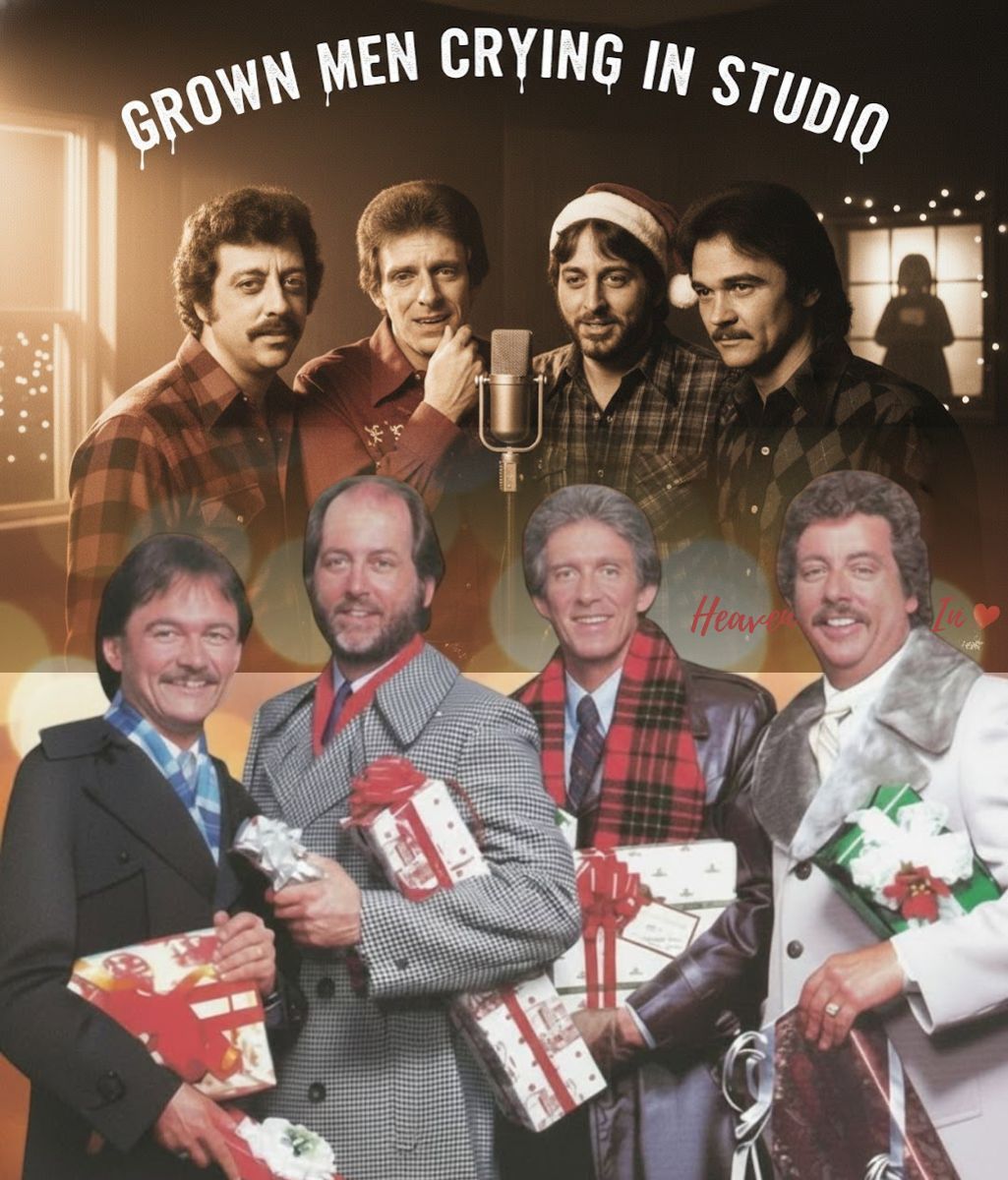

THE SONG THAT BROKE TOUGH COUNTRY HEARTS — STATLER BROTHERS’ TEAR-JERKING STUDIO MIRACLE!

It was late. The kind of late where even the neon in Nashville seems to whisper instead of shout. Inside a quiet, dimly lit studio just off Music Row, the Statler Brothers—Harold, Don, Phil, and Lew—gathered around vintage microphones with coffee cooling and lyric sheets shaking slightly in their hands.

The song was called “Christmas to a Little Girl.” A simple title. A sweet arrangement. But what happened when they hit “record” was anything but ordinary.

The Statlers weren’t new to studio magic. They had weathered every kind of stage, storm, and standing ovation, country music’s steadfast quartet with harmony tighter than blood. But this time, something changed.

As the opening chords hummed from the piano, the first verse fell to Don—his voice steady, worn like an old coat. But by the second line, it was trembling. Harold’s legendary bass, usually a rock, grew quieter, like a father trying not to break in front of his children. Lew’s tenor, gentle and sincere, softened to a hush. Phil, the heart of the group, barely made it through his part without his voice catching entirely.

In that moment—grown men, old friends, road-worn and whiskey-steeled—wept like children.

The song wasn’t flashy. It didn’t chase radio trends. But its message hit like a freight train wrapped in ribbon: the innocence of Christmas through the eyes of a child, sung by men who had long felt the weight of time, fame, faith, and loss.

Each line painted a picture so vivid—stockings hung too early, cookies cooling on the counter, soft giggles echoing down a hallway lit only by tree lights. But beneath every word was a deeper ache: the years lost, the daughters grown, the parents gone.

They weren’t just singing about Christmas. They were singing about everything they wished they could hold onto a little longer.

And then something happened in the room.

The kind of thing producers don’t speak about.

The kind of thing you can’t fake with mixing or gear.

Time froze.

No one moved. No one breathed. And for a moment, even the tape machine seemed to pause, letting that final harmony hang in the air like a prayer.

“And may she always find Christmas

In the arms that held her near…”

There it was.

A line so tender it broke through armor.

When they finished, the room remained silent. No high-fives. No playback requests. Just four men staring at the floor, trying to collect themselves. The engineer—a seasoned veteran—quietly stepped out of the booth and wiped his eyes.

“I’ve recorded a lot of voices,” he later said. “But that night… I think I heard heaven get closer.”

The Statlers would go on to perform that song only a handful of times. They never tried to recapture that studio moment—because they knew it couldn’t be recaptured. It wasn’t just a take. It was a testimony.

To family.

To time.

To the kind of love that hurts and heals in the same breath.

Fans who have heard the restored version describe it as “a memory set to music,” a track that feels like sitting beside your father on Christmas Eve or seeing your little girl asleep in the glow of the tree. It doesn’t just stir emotion—it undoes you.

Because that’s what The Statler Brothers did best—not just sing songs, but give voice to the parts of us we forget how to say out loud.

And in “Christmas to a Little Girl,” they gave us more than a melody.

They gave us a miracle caught on tape.

One quiet night.

Four weathered voices.

And a song so soft, it cracked the hearts of country’s toughest men.

Some music fades.

This one still whispers in December winds.