THE MONKEES: FROM SITCOM EXPERIMENT TO POP-CULTURE LEGEND — THE UNTOLD STRUGGLES BEHIND THE SMILES (1966–1968 AND BEYOND)

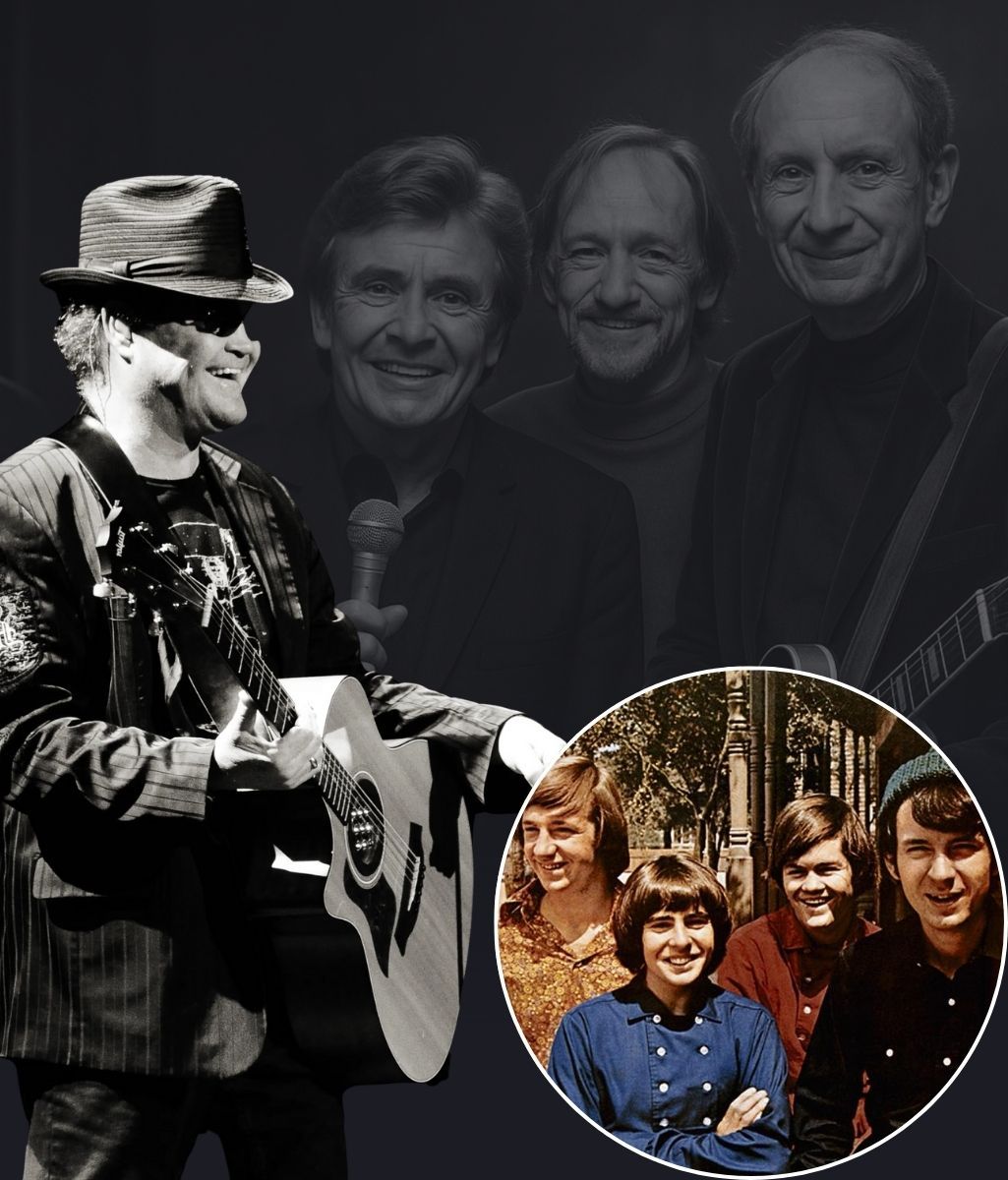

What began as a television concept became one of the most astonishing pivots in popular music. The Monkees — Micky Dolenz, Davy Jones, Michael Nesmith, and Peter Tork — were assembled for an NBC sitcom in 1966, yet within months they were topping charts, touring to frenzied crowds, and outselling the biggest artists on earth. Their ascent looked effortless on screen; off camera, it was a battle for identity, artistry, and simple human peace.

The blueprint was drafted years earlier. Producer Bob Rafelson first toyed with a music-comedy idea in the early 1960s, later partnering with Bert Schneider at Screen Gems to finally sell the show in 1965. Inspired by The Beatles’ films, the pair didn’t form a band in the usual way; they cast one. Trade-paper ads brought a stampede of hopefuls — hundreds auditioned — and the chosen four delivered precisely what television demanded: charisma, comic timing, camera ease, and, in at least two cases, serious musical chops. Music executive Don Kirshner (then a powerhouse song-placer) oversaw the show’s recordings, with the early plan calling for pre-recorded tracks and the actors primarily on vocals.

Then something unexpected happened. The “fictional” band became a real sensation. “Last Train to Clarksville,” “I’m a Believer,” and “Daydream Believer” didn’t just prop up episodes; they conquered radio. The TV series — quick-cut, fourth-wall-breaking, and zany — won an Emmy for Outstanding Comedy Series, and the music exploded far beyond the frame. On early tours, the reaction bordered on pandemonium; reports of fainting fans and overwhelmed venues only fed the momentum. They were nicknamed the “Prefab Four,” but the numbers — and the noise — said otherwise.

Success, however, sharpened the central conflict: control. By January 1967, with “More of the Monkees” arriving heavy with outside material, Peter Tork and Michael Nesmith bristled at the idea of being stars who couldn’t steer their own sound. The group pushed back, demanding to play, write, and shape their records. The result was “Headquarters” — a turning-point album performed by The Monkees themselves — followed by “Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd.” The victory was artistic and symbolic: they had evolved from TV characters into musicians who could carry the room without a laugh track.

But creative freedom comes with creative friction. Differences in taste, pace, and purpose widened. The TV series ended after two seasons. In 1968, the band took a daring swing with the feature film “Head,” written with a then-up-and-coming Jack Nicholson. Psychedelic, plotless, and satirical, it confounded audiences and was poorly marketed — a cult artifact today, a commercial thud then. Peter Tork, exhausted and disillusioned, soon departed. By 1969–1970, Michael Nesmith also moved on, and Davy Jones and Micky Dolenz fulfilled one last contractual album together. The initial dream had fractured under the weight of expectations and extraordinary speed.

The post-peak years were not gentle. Peter Tork wrestled with substance issues, money troubles, and reinvention — at one point teaching school before rebuilding a music career. Michael Nesmith weathered tax woes, personal upheaval, and a mysterious health ordeal years later that he attributed to prayer, patience, and time. Micky Dolenz kept working in television, theater, and voice acting; Davy Jones remained beloved, a perennial crowd-pleaser until his sudden passing years later. The headlines fans saw — reunions, revivals, reruns — barely hinted at the private toll that fame and fragmentation can exact.

And yet the story refused to end in ashes. In 1986, MTV marathon-aired the original series, sparking a full-scale renaissance. A reunion tour roared to sell-outs, and the single “That Was Then, This Is Now” introduced the group to a new generation. In the 1990s, the album “Justus” put the four names on one label again, written and produced by the band themselves. Into the 2010s, anniversaries and albums kept the catalog alive; “Good Times!” (2016) — featuring contributions from the surviving members and a vintage vocal from Davy Jones — debuted high on the charts, proof that the songs still breathed.

Beneath the applause lay complicated friendships. Creative disagreements never fully disappeared; tours saw comings and goings as personalities and priorities shifted. There were heartfelt tributes as well — nights when Micky Dolenz and Michael Nesmith stood under the lights and sang not just for the audience, but for absent friends. Those performances made clear what the sitcom once hinted at: that the best harmony isn’t just musical; it’s human.

In the origin story, the critics had a point: The Monkees weren’t formed “organically.” But the conclusion belongs to history, not the hecklers. The band took a manufactured premise and transcended it — fighting for authorship, earning their instruments on the records, and etching indelible pop into the culture. Their catalog — from “Last Train to Clarksville” to “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” from the theme’s bright snap to the ache of “Daydream Believer” — remains a time capsule of 1960s innocence and wit that still sparks joy.

The tragedies and trials matter, too. Substance struggles, bruised egos, and the lonely spaces left by fame are all part of the ledger. But so are the triumphs: Emmys, multi-million album sales, the audacity of “Headquarters,” the risk of “Head,” and the revival that proved the music was bigger than any format. For all the tension, there were also countless nights when four voices — first on a soundstage, then on a stage-stage — lifted a room into pure delight.

Nearly six decades on, the verdict stands. The Monkees were a show, yes — and also a sound, a spirit, and a living argument that great pop can come from the unlikeliest places. They began as an idea; they became a band; they ended up a legend. The smiles were real, the struggles were realer, and the songs — the songs are forever.